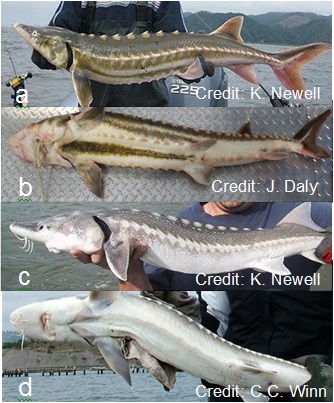

Figure 1. Lateral and ventral morphological differences

between green sturgeon (a-b) and white sturgeon (c-d).

White sturgeon and green sturgeon are California's only sturgeon. White sturgeon are vastly more common than green sturgeon, such that most anglers will never see a green sturgeon in the wild.

Sturgeon are among the largest and most ancient of bony fishes. They are highly specialized, containing such features as a heterocercal tail, fin structure, jaw structure, spiral valve intestine, and spiracle. They have a cartilaginous skeleton and possess several rows of large ossified plates, called scutes, instead of scales. Sturgeon are highly adapted for feeding on bottom-dwelling animals, which they detect using a row of extremely sensitive barbels on the underside of their snouts. Sturgeons also have electrical sensory organs on their snout, called Ampullae of Lorenzini, that help them detect prey in murky waters and perhaps guide them during their coastal migrations, as observed in hammerhead sharks (Klimley 1993). They can protrude their long and flexible mouths into the substrate to slurp up food.

Only two sturgeon species reside on the west coast of North America, the green sturgeon,

Acipenser medirostris, and the white sturgeon,

A. transmontanus (Moyle 2002). Green sturgeon were first described by Ayres (1854) from San Francisco Bay. Green sturgeon may be distinguished from the sympatric white sturgeon (Figure 1) by their olive green color, their barbells (which are closer to the mouth than the tip of their snout), a prominent green stripe on the lateral and ventral sides of their abdomen, the presence of relatively sharp scutes, differences in number of lateral scutes, the presence of one large scute behind the dorsal and anal fins (which is absent in white sturgeon), and the location of the vent (North et al. 2002).

References

Ayres, W. O. 1854. Descriptions of three new species of sturgeon San Francisco. Proceedings of the California Academy of Natural Sciences 1:14-15.

Klimley, A. P. 1993. Highly directional swimming by scalloped hammerhead sharks, Sphyrna lewini, and subsurface irradiance, temperature, bathymetry, and geomagnetic field. Marine Biology. 117:1-22.

Moyle, P.B. 2002. Inland Fishes of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 502 pp.

North, J.A., R.A. Farr, and P. Vescei. 2002. A comparison of meristic and morphometric characters of green sturgeon Acipenser medirostris. J. Applied Ichthyology 18:234-239.